‘Educate yourself’: Mom warning parents of MIS-C’s link to COVID-19 after son’s near-death experience

Mother shares sons near-death experience with MIS-C

MIS-C is an illness seen in some young children after they've recovered from COVID-19. Rohen was in the hospital for days and still has months of recovery ahead of him - and his mother is sharing their harrowing experience as a warning to other parents.

A North Carolina mother is encouraging other parents to be aware of MIS-C and its link to COVID-19 in children after her son’s near-death experience.

Nickey Reato-Stamey’s 12-year-old and only son, Rohen, has suffered for over a month from the crippling side effects from the infection that is associated with COVID-19 in children. MIS-C is an abbreviation for multisystem inflammatory syndrome.

After Reato-Stamey and her whole family got COVID-19 in December of 2020, she was hopeful that riding out the virus from home would be the end of it. But unfortunately, that’s not what happened.

"When he (Rohen) was sick with COVID, it was very brief. It was just one evening with a really quick fever and he was just glassy-eyed," Reato-Stamey said. "But other than that, it was super quick. He was not symptomatic for long, at all."

Rohan in the hospital.

RELATED: COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: What parents need to know

Reato-Stamey said she’s unsure how her family got sick, as they’d been taking precautions since her mother died after contracting COVID-19. And as the family continued to grieve the loss of their loved one, they were dealt another blow — Rohen got a sudden fever.

"Almost to the day, a month later on Jan. 16, which was a Saturday evening, he spiked a really high fever," Reato-Stamey said. "The thermometer had said that it was 105.9 and I thought, ‘That can’t be.’ I thought my thermometer was wrong. They were the point-and-shoot thermometers and I thought, ‘Ok, heard some stuff about these things not being so super accurate. There’s no way he has a 105.9 fever.’"

Reato-Stamey said she gave her son Tylenol to reduce his fever, which eventually made him comfortable enough to sleep through the night. But little did the family know, their health nightmare was only beginning.

RELATED: CDC: Fully-vaccinated people can gather without masks, should still cover face in public

The next morning, Rohen’s fever was still high.

"I contacted a nurse. She said to do the cool rags, alternate Advil and Tylenol every three or four hours and, as long as he was responding to the medication, that he should be ok. So I would give him the medication and the fever would come down and then it would go back up and come down and go back up," Reato-Stamey said.

And by Monday morning, her son was not getting any better, so she decided it was time to take more drastic actions.

"Monday morning rolled around and I said, ‘That’s enough.’ Thirty-six hours or whatever of a high fever," she said. "I contacted his pediatrician. By the time we got to the pediatrician, their thermometer was reading 105.9. They treated him for the fever, they gave him Tylenol too, they put some rags on his forehead. He was vomiting by that time and just very unwell."

RELATED: COVID-19 vaccines: When can children get vaccinated?

Rohen’s pediatrician began running tests, specifically for the flu, strep and adenovirus.

"(The doctor) said, ‘Kids with COVID are not presenting this way, so I don’t think it’s COVID-19,’" Reato-Stamey said. "And I said, ‘No me either because he’s already had COVID.’ He didn’t say anything about MIS-C; I don’t even think that was on his radar."

All of Rohen’s tests came back negative, so his pediatrician told Rohen’s mother to bring him back home and continue to treat him with fever-reducer medications, keep him hydrated and continue to monitor his symptoms. The doctor also wanted to see Rohen again the next day to run more tests.

Rohen in the hospital being treated for MIS-C. (Nickey Reato-Stamey)

RELATED: Teachers, child care workers nationwide can now sign up for COVID-19 vaccine

But by the next morning on Tuesday, Rohen was still "very, very sick," according to his mother. So instead of going to see her son’s pediatrician as planned, she decided it was time to bring her son to the hospital, and Rohen’s pediatrician issued a direct admission for him.

Medical staff immediately started running tests, and that’s when his mother heard the acronym MIS-C for the first time.

"Once we got there, they started saying, ‘We’re going to run some lab work but, there’s this thing called MIS-C, which is multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children,’ and he’s checking off some of those boxes, but not all of the boxes, so they weren’t ready to commit to that diagnosis at that time," Reato-Stamey said.

The night of his first hospital stay, Rohen took a "sharp downward turn" for the worse, according to his mother.

RELATED: When will children be able to get COVID-19 vaccines? It depends on age

"He was not able to breathe, that’s when he had to be put on oxygen. The pericardial sac of his heart was beginning to fill up with fluid and the tissue to break down. His blood pressure plummeted, very quickly," she said.

Medical staff quickly scanned Rohen for blood clots and at that point, Rohen was officially diagnosed with MIS-C.

Rohen’s lungs were inflamed and full of fluid and his coronary arteries were enlarged and working overtime to help him survive this sometimes deadly illness.

Health care workers immediately moved Rohen to the PICU where his mother got the news she was dreading. Not only were doctors unsure if Rohen would survive, but they were also unsure of how to treat MIS-C.

RELATED: Vaccine rollout breeds mixed emotions, including guilt and envy

Rohen being treated by health care workers.

"They tried to get blood from him and the blood just had no oxygen in it, it looked like chocolate syrup coming through the vials. It was awful and really, really scary," she said. "The PICU doctors just said, ‘We just have to be really honest with you, we don’t know about this MIS-C stuff and we don’t have all the answers, we don’t have it all figured out, we don’t know what the long-term implications are. And, as of today, we cannot tell you your son’s going to be OK.’"

For the next five days, Rohen’s body continued to fight and eventually doctors were confident enough to say he was going to survive.

"I was fine with the treatment and whatever needed to go on, as long as it got us to that place where he was going to be OK. And it took about five days of treatment before they were willing to say, ‘I think he’s not going to die. I think we’re to a place where he’s not going to die,’" she said.

Rohen’s mother commended the doctors that, despite not being well-versed about MIS-C, "they were great at trying to figure it all out."

After conferring with other doctors, cardiologists and health experts throughout the state of North Carolina, Rohen was put on an IVIg (intravenous immunoglobulin treatment), which is used to treat Kawasaki disease. Kawasaki disease, also known as Kawasaki syndrome, is an acute febrile illness of unknown etiology that primarily affects children younger than 5 years of age, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

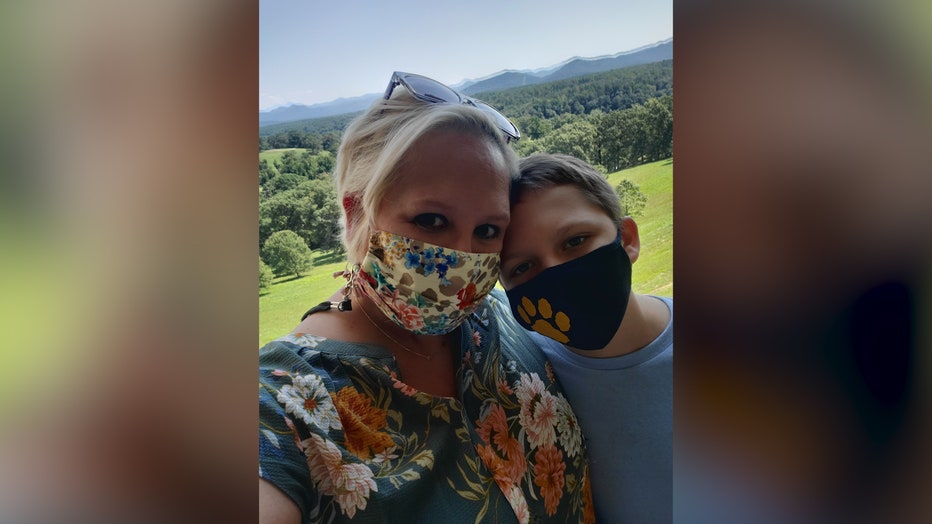

Nickey (left) and her son, Rohen (right).

RELATED: Single test to distinguish COVID-19, flu viruses gets FDA approval

Slowly, Rohen started to get better, but not without the help of thousands of milligrams of medicines and steroids being pumped into his body.

And now, nearly five weeks after his terrifying ordeal, Rohen is still facing a plethora of issues including myocarditis, which "is an inflammation of the heart muscle that decreases the ability of the heart to pump blood normally," according to Harvard Health. He’s also in physical therapy to help build back his strength.

"He’s not himself, 100%. He’s a lot better, a lot better. But, it’s been a nightmare," Reato-Stamey said.

RELATED: Airline industry pushes US to standardize health papers

Rohen is now at home recovering with the help of his family but doctors say they don’t think he’ll be back to his 100% self for another six months, according to his mother.

"Rohen can, maybe, take 10-minute walks? And he’s built up to that, before that we couldn’t even get him up the stairs of the porch to get him in the house," Reato-Stamey said. "So he has ongoing physical therapy to continue to build his core, he has an EKG and an echocardiogram every other week. In April he has an MRI. He has a heart monitor and he’ll have a stress test."

"He can’t go to school. He can’t participate in his soccer season. He can’t be out in public because if he were to get any kind of other virus or anything else that would make him febrile, it could be fatal. So, it’s radically changed his life as a 12-year-old. It didn’t just end the day we checked out of the hospital," Reato-Stamey said.

Reato-Stamey said as her son continues to cope with recovering after having a rough year, she’s seen the light dim from her son’s spirit.

Nickey pictured alongside her son, Rohen.

RELATED: Workers worry about safety, stress as states ease mask rules

"I’ve explained Rohen as being this vibrant child and, of course, I’m his mom so I’m biased and people probably won’t believe me when I say it but, he really is, or used to be, the bright spot in any room. There’s just a glow around him, an aura of light around the child. And he’s so witty and he’s so kind and he’s so gentle and he’s so sweet. But he’s been through a lot and it’s definitely had impacts on him mentally," Reato-Stamey continued.

Reato-Stamey said that her son has always been gentle and sweet, even as she went through her own health challenges.

"I had really serious breast cancer that we went through as a family and then in December, we lost my mother and then he got so sick. So it’s been hard to see that light fade. The light has dimmed, for sure. He is still kind and he is still loving and he is still dear and he is still funny and all of those things, but it’s leveled down. It hasn’t leveled up," she added.

Reato-Stamey hopes that her son’s frightening experience with MIS-C will not put the fear into parents that their children will get it, but more so to warn them that it is real and could happen without any warning.

"So if your child develops a very high fever, just out of the blue, take your child to a medical provider. Advocate for the right kind of lab testing; mention MIS-C, especially if they’ve had COVID-19. Wear your mask. Go to school and do all the things but wear your mask, wash your hands, stay 6 feet apart, and just be good to one another. Let’s just be good, let’s be kind."

For parents who want to stay ahead of the curve and stay informed, Reato-Stamey suggested monitoring the CDC’s website that specifically speaks upon children and COVID-19 as well as MIS-C.

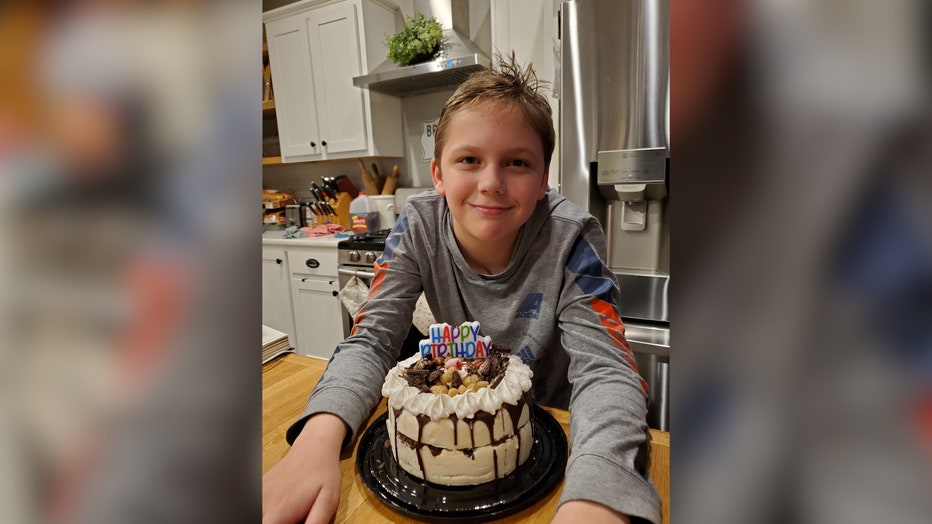

Rohen pictured with his birthday cake on Dec. 30. (Nickey Reato-Stamey)

RELATED: Scientists say COVID-19 could become endemic but pose less of societal threat over time

"I wish I had known more earlier on about what could happen. I feel like the COVID situation for kids was downplayed a lot. So, the length of time that it takes for you to watch a TikTok video, you can read the CDC webpage so, you do have time to educate yourself," Reato-Stamey said.

Experts have warned that significant community transmission of COVID-19 will likely increase the prevalence of MIS-C. Parents should monitor children for telling signs of MIS-C such as fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, inflammation of the skin, eyes, hands, or feet, skin rash, or lips or eyes that appear red. Some children have puffy hands or feet, while others present enlarged lymph nodes.

As of March 9, more than 2,600 MIS-C cases have been reported nationwide, disproportionately affecting minority populations. More than 30 children have died in the U.S. after developing the condition, according to estimates from the CDC.

FOX News contributed to this report.