Clive Sinclair, pioneer of affordable home computers, dies at 81

LONDON - Clive Sinclair, the British inventor and entrepreneur who arguably did more than anyone else to inspire a whole generation of children into a life-long passion for computers and gaming, has died. He was 81.

Sinclair, who rose to prominence in the early 1980s with a series of affordable home computers that offered millions their first glimpse into the world of coding as well as the adrenaline rush of playing games on screens, died on Thursday morning after a long battle with cancer.

Though ailing, his daughter Belinda Sinclair said, he was still working on inventions up until last week.

"He was inventive and imaginative and for him it was exciting and an adventure, it was his passion," she told the BBC.

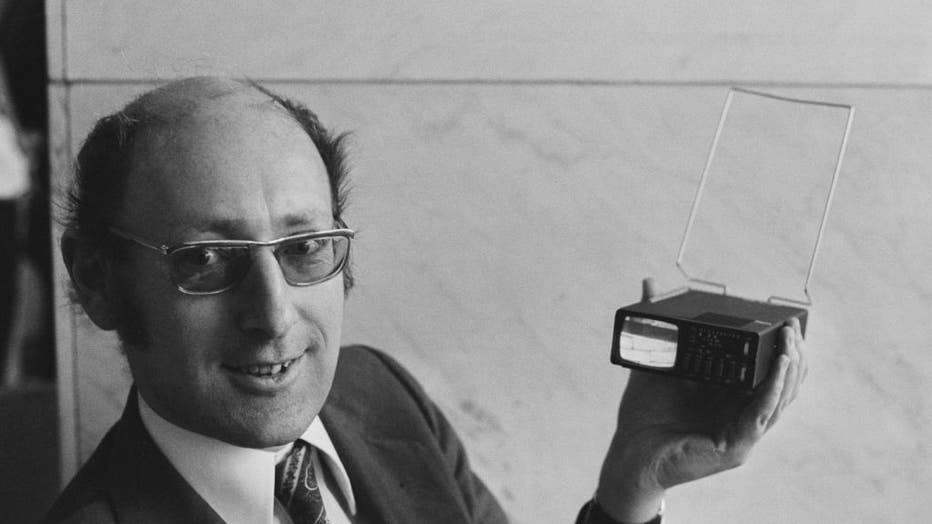

British entrepreneur and inventor Sir Clive Sinclair holding a Sinclair MTV1 Microvision pocket television in London, England, in January 1977. The set was developed by Sinclair's company Sinclair Radionics. (Photo by Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/

Born in 1940 in the plush southwest London suburb of Richmond, Sinclair left school at the age of 17 and became a technical journalist before deciding he — and the world — would be better off if he used his brainpower to come up with inventions himself.

Aged 22, he formed Sinclair Radionics, his first company, making mail-order radio kits, including the smallest transistor radio in the world. He really came to prominence in 1973 with the world’s first pocket calculator, before turning his sights and passions into transitioning the world of computers to the confines of the home.

He became a much-beloved figure in Britain and around the world, for his successes — as well as occasional failures. Tributes poured in from modern-day equivalents such as Elon Musk as well as countless "normal" people who first got hooked on computers and gaming via one of Sinclair's inventions.

Sinclair launched his first affordable consumer computer in 1980, which cost less than 100 pounds ($135). The ZX80, which could subsequently be upgraded to the ZX81 with a bit more memory, may not have been sophisticated in today's terms, but it broke new ground, opening up a world of new opportunities.

"The ZX81 was my introduction to computing and I loved it!," the science broadcaster Prof. Brian Cox said in a tweet.

In 1982 came the iconic ZX Spectrum, which was certainly a step-change from its predecessors and which would not look too out of place today. Through the 1980s, it took its place in an increasingly crowded marketplace against the likes of the Commodore 64, the first Apple computers as well as those from Atari.

The Spectrum went on to become Britain’s best-selling computer. Not only did it help Sinclair become a multimillionaire, it made him a household name at a time the British economy was undergoing a radical transformation under then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1983.

"RIP, Sir Sinclair. I loved that computer," Tesla CEO Musk said in a tweet.

The benefits of the Spectrum — and its peers — were felt far and wide, leading to a boom in companies that produced software and hardware. Not to mention the shops that were selling these home computers and all their add-ons.

British business mogul Alan Sugar, who was one of the main protagonists in this new era of home technology with his company Amstrad, paid tribute to his "good friend and competitor."

"What a guy he kicked started consumer electronics in the U.K. with his amplifier kits then calculators, watches mini TV and of course the Sinclair ZX. Not to forget his quirky electric car. R.I.P Friend," he said on Twitter.

For many people, Sinclair will be best remembered for that "quirky" Sinclair C5, an ill-fated electric tricycle heralded as the future of eco-friendly transport but which turned out to be an expensive flop.

"It was the ideas, the challenge, that he found exciting," Sinclair's daughter said. "He’d come up with an idea and say, ‘There’s no point in asking if someone wants it, because they can’t imagine it.’"