You've heard about lake-effect snow but what about industrial-effect snow?

Chicago - If you live in McHenry County and saw a few flurries on Monday, chances are it was industrial-effect snow that drifted south out of Madison, Wisconsin.

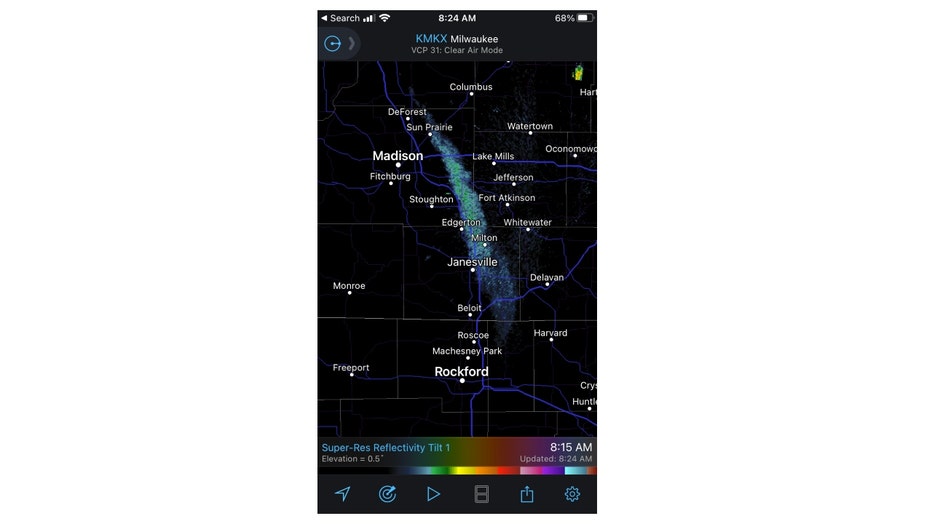

My colleague Mike Caplan and I noticed what was at first glance, a strange plume of snow that emanated from just northeast of Wisconsin's capital and extended all the way across the Illinois border. There weren't any typical meteorological culprits for it such as a front, storm system or even some weak upper-level energy passing overhead.

Mike zoomed in on Google Maps to the source area, where we discovered a power plant in Portage that could possibly be the cause.

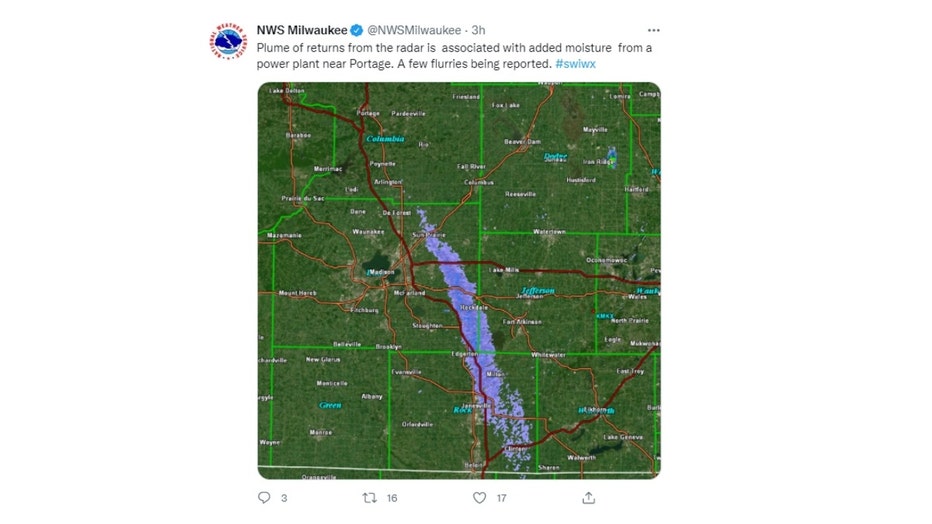

The National Weather Service in Milwaukee confirmed what we suspected on Twitter - this was industrial-effect snow. Steam from power plants can be cooled enough to squeeze out snowfall provided there is a sufficient difference in temperature between the steam and the air in the atmosphere around it. The same principals are at play that we see with more traditional lake-effect snow.

In Chicago's case, the water evaporating off of Lake Michigan's relatively warm waters supply the moisture source and all that is needed is to cool it off to the point of condensation and eventual snowfall if cold enough air is above the lake.

Industrial-effect snow or industrial-enhanced snow has been noted as far south as Amarillo, Texas. All that is needed is relatively warm, moist air from a source at the surface and cold enough air around it to produce snow.

A steel mill in Gary, Indiana has had a history of producing industrial-effect snow southeast of Chicago.